Background – 02

These recommendations are enormously influential, as they largely inform our ideas about healthy eating.

They also drive food and nutrition policy decisions, such as:

- The National School Lunch Program (NSLP)

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program educational programming (SNAP-ed)

- Special Nutritional Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC)

- Military food programs

- Nutrition support for the elderly

- Back-of-package labeling on packaged foods

- Dietary advice dispensed by doctors, nurses, dieticians, nutritionists, and other health professionals

Some questions have been raised about the Guidelines in recent years. Our two top concerns:

Are the Dietary Guidelines Intended for all Americans?

Congress stated that the Guidelines should be for the “general public.” Yet the agencies overseeing the Guidelines, the U.S. Departments of Agriculture and Health and Human Services (USDA-HHS) have interpreted this scope to mean that the Guidelines are only for “healthy Americans.”

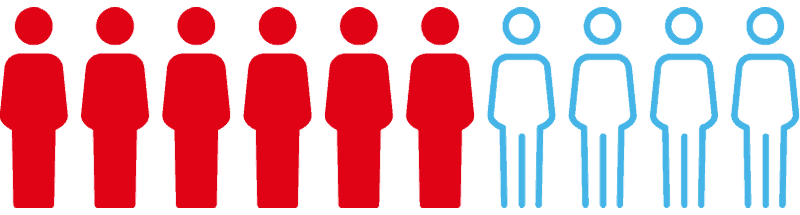

A majority of Americans were indeed healthy in 1980 – when the Guidelines were launched – yet today, this is no longer the case.

The continued focus by USDA-HHS exclusively on “healthy Americans” has grave ramifications and limitations, since:

The policy’s one-size-fits-all approach excludes hundreds of millions of Americans with nutrition-related diseases.

This narrow focus disproportionately impacts minority communities, including African Americans, Hispanics, and indigenous communities. These communities are more reliant on federal nutrition programs and also suffer from higher rates of chronic disease.

In fact:

It is therefore critical that the Guidelines offer a diversity of dietary options for these communities. The danger of excluding so many of our citizens, including those who are most in need of reliable nutrition advice, is an urgent issue that needs to be addressed by our nation’s leading nutrition policy.

Indeed, no less than the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, in a Congressionally mandated 2017 report, recommended that USDA-HHS should “broaden the scope of the Dietary Guidelines…

such that future editions focus on the general public across the entire life span, including all Americans whose health could benefit by improving diet…”

How Strong is the Science Supporting the Recommendations?

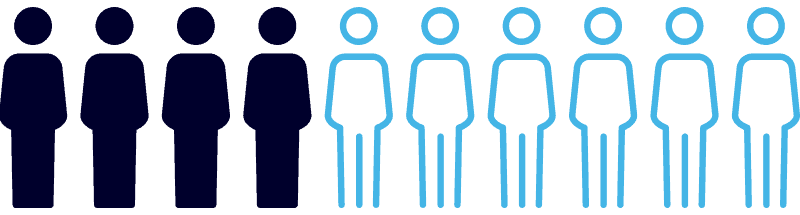

Highlighting the desperate need to fund public health nutrition research, just 20% of the newly-graded evidence informing the 2015 guidelines received a “strong” rating, according to standards set forth by the USDA-HHS. *

That 2017 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) recognized this problem and stated:

“To develop a trustworthy DGA, the process needs to be redesigned.”

NASEM recommended upgrading the the scientific review process for the Guidelines, to a state-of-the-art methodology that would ensure more reliability in the Guidelines process. NASEM said:

“The DGA has to be based on the highest standards of scientific data and analyses to reach the most robust recommendations.“

NASEM recommended: “A redesigned process,” including:

“more rigorous methodological approaches to evaluation of evidence…” such that analyses “be based on validated, standardized, and up-to-date methods and processes.”

Food4Health will work to ensure that the next iteration of the Guidelines will:

1) Do more to provide nutritional advice for all Americans, not just those deemed to be “healthy.”

2) Be trustworthy and based in a rigorous, state-of-the-art scientific review methodology.

The Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee assigns a grade to the quality of the science for each question studied (e.g., what is the relationship between a vegetarian diet and cardiovascular disease?). There are four grading options:

I. “Strong” represents a conclusion statement supported by a “large, high-quality body of evidence that addresses the topic.” Ideally, this should include multiple clinical trials, since this is the type of study that can demonstrate cause-and-effect. The level of certainty should be high, unlikely to change, and generalizable to the population of interest.

II. “Moderate” represents a conclusion statement with sufficient evidence, but the level of certainty is restricted by the amount of evidence, inconsistency in the findings, or methodological or generalizability concerns.

III. “Limited” represents a conclusion statement that is substantiated by insufficient evidence, and certainty is severely restricted by the amount of evidence, inconsistent findings, or methodological or generalizability concerns.

IV. “Grade not assignable” means a conclusion statement cannot be drawn due to the lack of evidence, or the evidence that is available has severe methodological concerns.